Schaulager is presenting the first comprehensive exhibition of work by the radical British video artist and filmmaker Steve McQueen. For the first time, more than twenty video and film installations, photographs and other selected work will be on view in a larger context. For this unprecedented show, two floors of the Schaulager have been architecturally transformed into a custom-built City of Cinemas. Interior and exterior spaces with viewing apertures, mirrors and variations in light intensities and degrees of darkness provide surprising insights into the artist's work.

“Steve McQueen” is an experience quite unlike a conventional exhibition. Works with moving images make greater demands on the viewer's time than paintings or sculptures. Therefore, the admission tickets are valid for three visits to the exhibition. Much like going to the cinema, the exhibition is open from afternoon to evening. Every Thursday evening is Schaulager Night: the exhibition, with accompanying special events, is open until 10 p.m. with a selection of tasty refreshments available in the café bar. Additionally, there is an attractive programme of tours, talks, filmscreenings, workshops and a symposium. The details and dates are listed in the exhibition booklet, handed out for free at Schaulager, as well as on this website, which is regularly updated. We wish you a fascinating visit to the exhibition “Steve McQueen”.

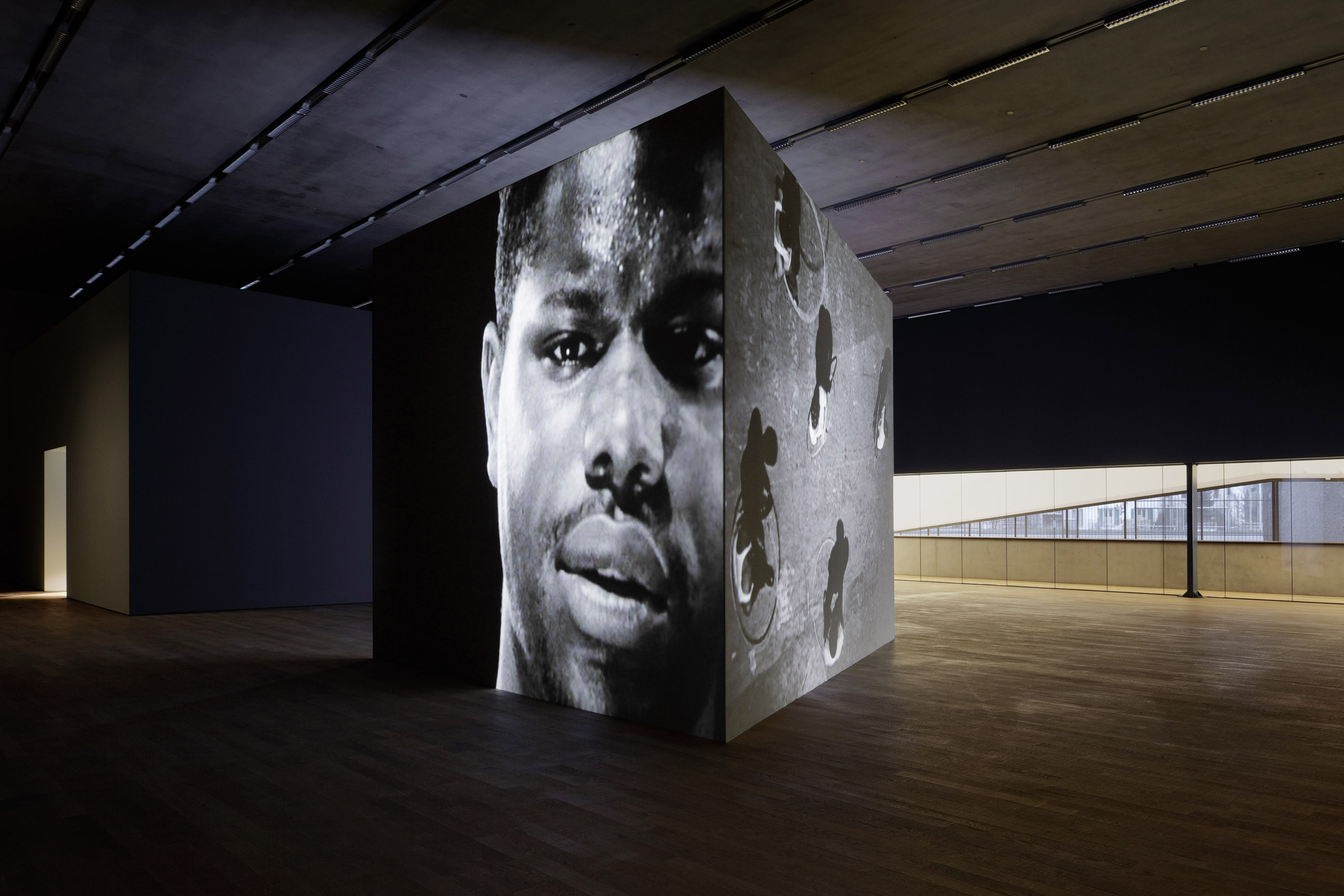

Installation view: Steve McQueen, Static, 2009, installation view, Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation, Gift of the president 2012, on permanent loan to the Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel, Courtesy the Artist © Steve McQueen, photo: © Tom Bisig, Basel

Installation view: Steve McQueen, Charlotte, 2004, Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation, Gift of the president 2012, on permanent loan to the Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel, Courtesy the Artist © Steve McQueen, photo: © Tom Bisig, Basel

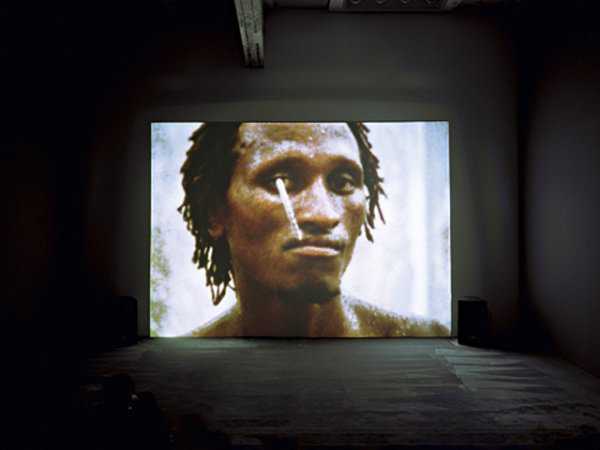

Installation view: Bear, 1993, installation view, Courtesy the Artist / Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris and Thomas Dane Gallery, London © Steve McQueen, photo: © Tom Bisig, Basel

Installation view: Steve McQueen, Five Easy Pieces, 1995, Courtesy the Artist / Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris and Thomas Dane Gallery, London © Steve McQueen, photo: © Tom Bisig, Basel

Installation view: Steve McQueen, Queen and Country, 2007-2009, Collection Imperial War Museums, presented by The Art Fund, Courtesy the Artist © Steve McQueen, photo: © Tom Bisig, Basel