Steve McQueen, Drumroll, 1998

Many of Steve McQueen’s works substantially impact the movement, direction and position of the viewer in space. They exert an inescapable pull, drawing us into their dynamic, as in the radial force generated in Static, the first work encountered on entering the exhibition. On a screen suspended in space, we watch the images made by a camera circling around the Statue of Liberty and find the torque affecting our own steps. The sculptural quality of this piece is reinforced by having to walk around it in order to enter the darkened body of the exhibition. McQueen’s handling of movement, its almost intrusive immediacy, already informs the early films Bear, Five Easy Pieces and Just Above My Head. For the first time, instead of being presented separately in self-contained spaces, the three films are screened simultaneously on the central square of the City of Cinemas created for this exhibition. Their three-dimensionality is reinforced by a presentation that allows for multiple viewpoints, so that the sculptural parameters of body, volume and structure complement the cinematic factors of time and motion. In Bear, two men are wrestling in a circular play on proximity and distance, strength and restraint. In contrast, the rigorously composed images of various brief actions in Five Easy Pieces are oriented along vertical and horizontal axes. Just Above My Head, showing the artist’s head cropped at the bottom of the picture, pursues this formalistic aesthetic and provides a transition to Deadpan, a work McQueen made immediately afterwards as a tribute to Buster Keaton.

I like the film to be like a wet piece of soap –

it slips out of your grasp. You have to

physically move around, you have to readjust

your position in relation to it, so that it dictates

to you rather than you to it.

Steve McQueen

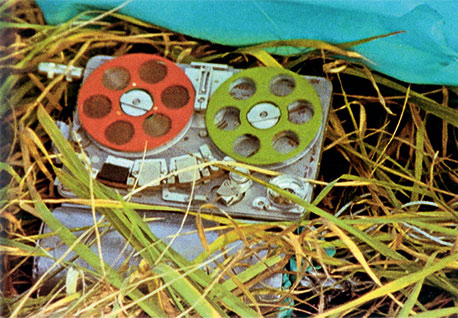

The artist’s body plays a performative role in both works, which are shaped and framed by the conspicuously positioned camera. McQueen almost falls out of frame in Just Above My Head, while in Deadpan he is literally framed by a window when the wall of a house collapses on top of him. In Drumroll McQueen’s camerawork is even more experimental: he attached three cameras to an oil barrel and rolled it through the streets of New York — an automatic image-finding mechanism. Sound and image reveal the immediacy of the unfiltered production process. The film is literally rolling.

The resulting triptych, revolving in three directions, divorces the viewer entirely from the camera positions. In view of these twirling images, we can no longer establish a fixed viewpoint; the world is shown as only a camera can see it. In the video installation Pursuit, finally, the mirrored walls completely undermine any sense of space, and the projection of reflected light multiplied in them deprives the viewer of all solid ground.