Approximately two hundred works from the Kunstmuseum Basel, together with others from the Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation and private collections, have left their familiar surroundings for a time and found a home at Schaulager. A large store of images, each of which was chosen for its own sake – hand selected, explicitly desired, considered particularly beautiful, particularly attractive or particularly mysterious.

Released from the museum’s ordering system, these images can be seen in a different light at Schaulager. Some of them have been preserved for the exhibition as still unpolished raw material, only roughly sorted. Spread out on a monumental wall, the pictures hang next to, beneath or above one another, as an enticing treasure for the imagination. This wall provides the framework for the interior spaces of the exhibition.

The other, larger group of resettled works are installed as a coherent installation in these interior spaces. The connections are, however, not produced based on the model of a classical museum hanging. Rather, the result was a different, new narrative, or better: an essay of pictures. It evolved, image by image, by means of diverse and unexpected relationships and numerous dialogues that ensued between the works, until finally the essay ‘Holbein to Tillmans’ took shape.

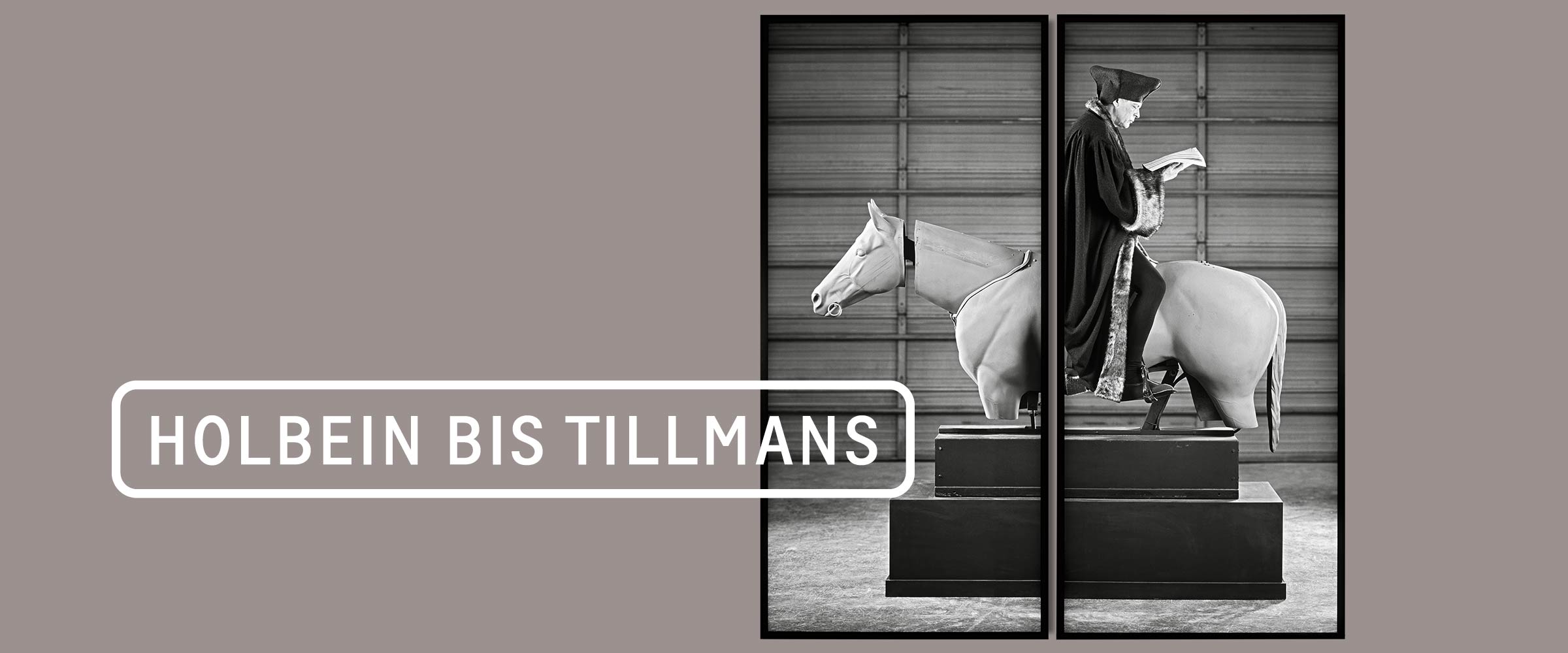

Hanging at the entrance to the exhibition is the monumental light box Allegory of Folly by the Canadian artist Rodney Graham. Sitting on a mechanical horse once used to train jockeys is a man, the artist himself, dressed in old-fashioned clothing: a coat with fur trim. He is sitting backwards on the horse and engrossed in reading a thick book. The image alludes to a portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger depicting Erasmus of Rotterdam, the author of the famous treatise ‘Praise of Folly’ as a half-length figure in profile. Allegory of Folly acts as a kind of guide to the exhibition. The juxtaposition of a work from the sixteenth century and a large-format black and white photograph from 2005 demonstrates exemplarily that old does not necessarily mean past; rather, an old painting seen with today’s eyes can suddenly become contemporary again. The figure of the man sitting backwards on a horse demonstrates that looking backwards is part of looking forwards, that what will come is connected to what was. And we stand in the middle of it all, contemplating the moment and absorbed by the present, just as the reading figure shows.