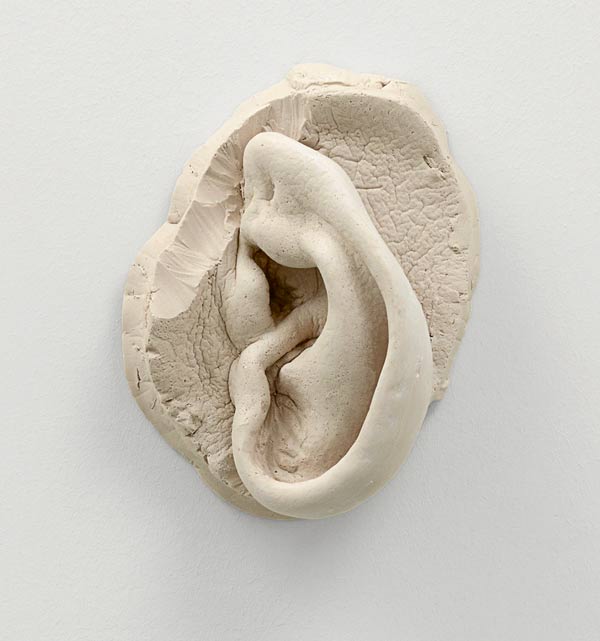

Robert Gober, Untitled, 2008

Cast gypsum polymer, 38 × 26.5 × 15.5 cm, Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation, on permanent loan to the Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel, Foto: Tom Bisig, Basel, © Robert Gober

The cast of an enlarged ear, which looks as if it had been cut out of flesh, is mounted upside down on the wall. The wrinkled skin, furrowed and full of pores, evokes memories of a scientific specimen or a death mask.

Enlarged body parts are unusual in Gober’s oeuvre. His casts of a child’s leg, breasts, or a torso are usually in 1:1 scale. In contrast, this oversized ear represents a particularly tender, sensitive, and intricately structured body part, divided into an outer ear, the visible auricle with a spiral- shaped protrusion leading to the middle ear and its three ossicles (hammer, anvil, and stirrup), and the inner ear, where sounds are converted into nerve impulses. Especially in Gober’s universe, this convoluted body part is sculpturally intriguing as a striking metaphor not only for the link between inside and outside, but also for the constant need to find balance.

The ear is a venerable subject matter in art: think of Van Gogh’s self-mutilation or the severed ear that plays a role in the opening sequence of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986). “Yes, that’s an ear, all right,” the detective says laconically on coming across the organic finding. Such laconic brevity applies equally to the disquietude hovering around Gober’s sculpture.

Robert Gober (b.1954, Wallingford, Connecticut, USA) has created an oeuvre that touches on socially sensitive issues such as sexuality, religion, and power since the 1970s. In staging his work, Gober’s art of isolation and imitation invests even the most ordinary objects – a sink or a dog bed – with several, often disconcerting layers of meaning. The essence of his work always rests on the act of making it. Robert Gober lives and works in New York.